The One First Long Read: The History of Certiorari

The first thing to say about “certiorari” is that lawyers can’t even agree if the word has four syllables or five. We often just shorthand it to “cert.” to save everyone the trouble. But however you pronounce it, there’s no denying the central role certiorari has played in the evolution of the Supreme Court as an institution, and the Court’s ability, for better or worse, to operate as it does today. In this first installment of the One First “Long Read,” we take a brief tour through the history and evolution of this obscure but critically important procedural device.

As law professor Ed Hartnett wrote in 2000, February 13, 1925 was the day on which “the modern Supreme Court was born.” No major decision was handed down on that date; no new Justice took the (two) oaths of office. Rather, it was on that otherwise nondescript Friday that President Calvin Coolidge signed into law the Judiciary Act of 1925—known then and now as the “Judges’ Bill,” entirely because it was the judges (technically, the Justices) who were behind it.

The Judges’ Bill fundamentally transformed the Supreme Court’s docket. For the Court’s first 101 years (from 1790 to 1891), the Justices had no discretion over whether or not to hear an appeal. Congress repeatedly tweaked which cases could be brought to the Supreme Court, but everyone understood that the Court’s “appellate jurisdiction” in whatever cases Congress prescribed was “mandatory”; if the Justices could hear an appeal from a lower state or federal court, then they had to do so.

In the decades after the Civil War, however, the Court’s docket (like that of lower federal courts) had exploded. Whether because of litigation arising out of the Reconstruction Amendments; the dramatic expansion of the federal government; the growing proliferation of federal regulation; or some combination of all three, the Supreme Court by one point in the late 1880s had over 1800 cases on its docket—with some estimates placing the Justices more than three years behind in clearing the backlog.

In the 1891 Evarts Act, Congress for the first time gave the Justices a modicum of control over their docket. In four classes of cases that were perceived at the time as relatively less important, the Court could choose whether or not to exercise jurisdiction by granting a “writ of certiorari.” And although the statute didn’t say so, it eventually became the Court’s practice (which, to this day, has never been codified in any statute or rule) that it takes four votes to agree to take up such an appeal, not five.

“To be more fully informed” in Latin, a writ of “certiorari” was an unusual but not unheard-of mechanism used by English appellate courts of the same era to take up cases from lower courts. The idea under the 1891 Act was to pick sets of cases then seen as generally insignificant, and spare the Justices of the need to explain themselves if a specific appeal was turned away. Thus began not only the “rule of four,” but also the practice of unexplained “denials” of certiorari—cursory orders in which permission to appeal one of those four types of cases was denied.

But the innovation of certiorari in the 1891 Act did very little to reduce the pressure on the Court’s docket. And Congress only added to that pressure in 1914, when it gave the Justices, for the first time, the power to hear appeals from state courts in cases in which the state courts had ruled in favor of a federal claim (from 1790–1914, the Supreme Court could review only those state court decisions rejecting federal claims). Although these appeals, too, came via certiorari, now, they were only adding new cases to the Court’s docket.

Thus, by 1925, the Justices themselves (led by Chief Justice, and former President, William Howard Taft) were some of the loudest proponents of giving the Court more discretion over its docket—not just over new types of appeals, as in the 1914 Act; or unimportant types of appeals, as in the 1891 Act, but over all appeals.

Taft didn’t hide his motivations. In an influential 1908 article published while he was running for the White House(!!), he had argued that the Supreme Court’s function was not to resolve individual cases, but rather to “cover the whole field of law upon the subject involved.” In a 1910 speech, then-President Taft directly connected the vision of the Supreme Court as a general expositor of legal principles to discretionary review of specific appeals. And after joining the faculty at Yale Law School at the end of his presidency, now-Professor Taft explicitly urged Congress in 1916 to do away with the requirement that the Justices hear appeals except in cases involving interpretations of the federal Constitution.

For Taft, it wasn’t just that the Justices were overworked; it was that a Court without discretion to pick and choose its cases couldn’t truly function as a constitutional court, because it would forever be deluged and distracted by technical appeals that, whatever their significance to the parties, were inconsequential to the nationwide development of the law. A supreme court, in Taft’s view, was one that controlled its docket, and not one that was told which cases to resolve.

In the Judges’ Bill, Congress (largely) acquiesced in Taft’s vision. Under the 1925 Act, the Supreme Court would have discretion to decide whether to hear all appeals from the federal intermediate appeals courts (but would still have to hear appeals from state courts when the state courts rejected a federal claim). And in 1988, Congress would finish Taft’s work—giving the Court discretion even over those appeals from state courts, as well. Today, the only appeals that the Supreme Court must hear are the two categories of cases that Congress requires to be heard by special “three-judge district courts”: challenges to congressional reapportionment; and certain challenges to campaign finance laws, appeals from which go directly to the Justices. During the Court’s most recent Term (the October 2021 Term), exactly one of the 58 cases resolved through a signed opinion came from a three-judge district court (thanks, Ted Cruz!); the other 57 were all cases the Justices chose to decide.

The shift toward certiorari gave the Justices discretion to pick and choose which cases they decide based upon criteria that would be entirely up to them. But Taft took it even further. Contradicting representations he had made to Congress while testifying in support of the Judges’ Bill, the Court also quickly claimed the power to decide only specific questions within the cases they were choosing to hear.

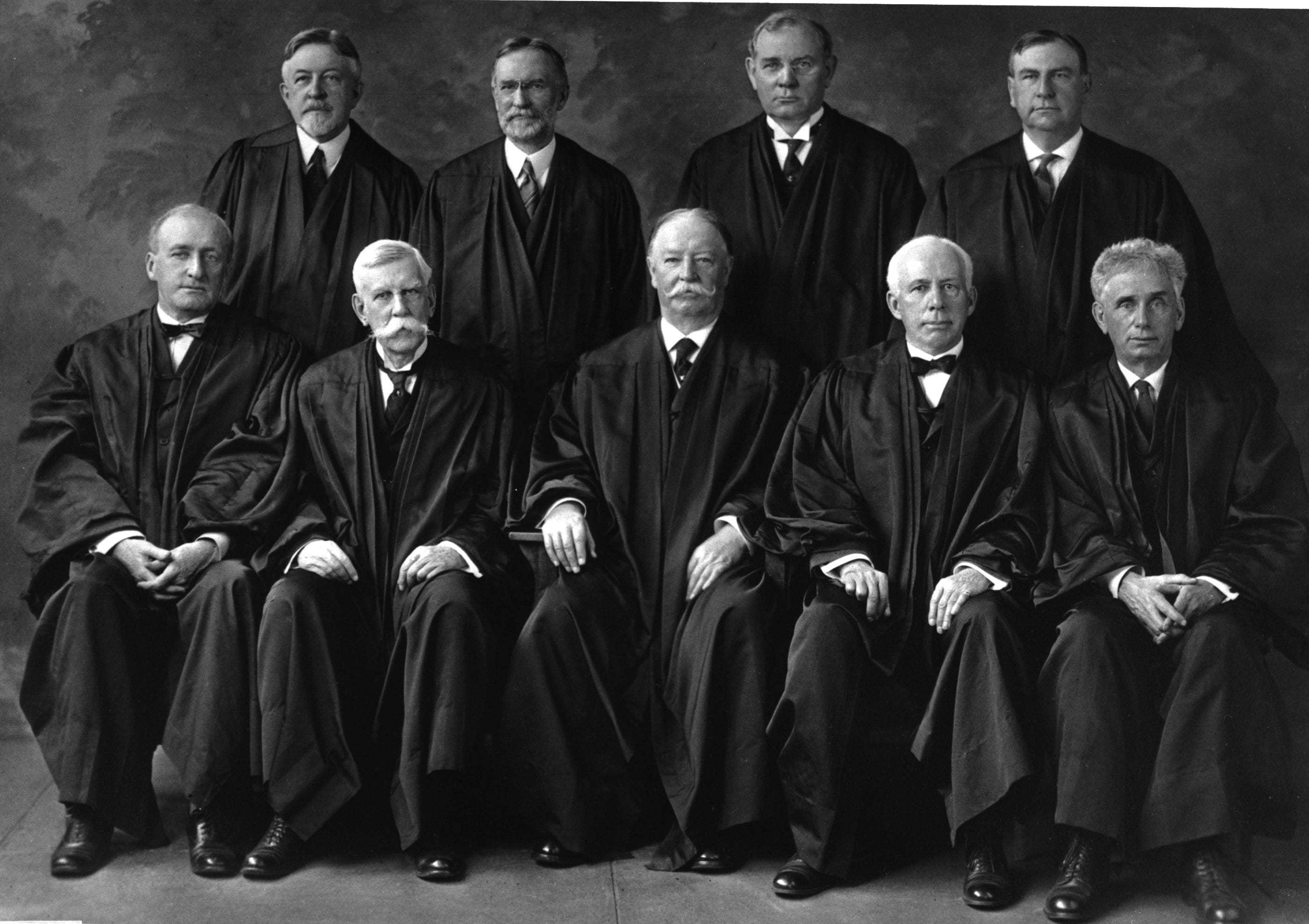

In one of the most prominent early examples, a 5-4 majority in Olmstead v. United States held that wiretaps of telephone calls did not require warrants under the Fourth Amendment even though, as three of the four dissenters argued, the case could have been resolved in Olmstead’s favor on other grounds. It was Taft, writing for the majority, who explained that the Court had agreed to resolve only the constitutional question. (Below is a picture of the Supreme Court that decided Olmstead in 1928; by tradition, Taft, as Chief Justice, is front-row center, and the rest of the Justices alternate to his right, then his left, in seniority order.)

That’s why today, a “cert. petition” (a “petition for a writ of certiorari”) must begin with the “Question(s) Presented” for review. Thanks to certiorari, the Supreme Court doesn’t actually hear appeals; it hears questions it has specifically chosen to hear within appeals. And in a growing number of cases, the Justices will even write their own questions when granting certiorari (as in the major Second Amendment case the Court decided this June), rather than relying upon the questions presented by the parties.

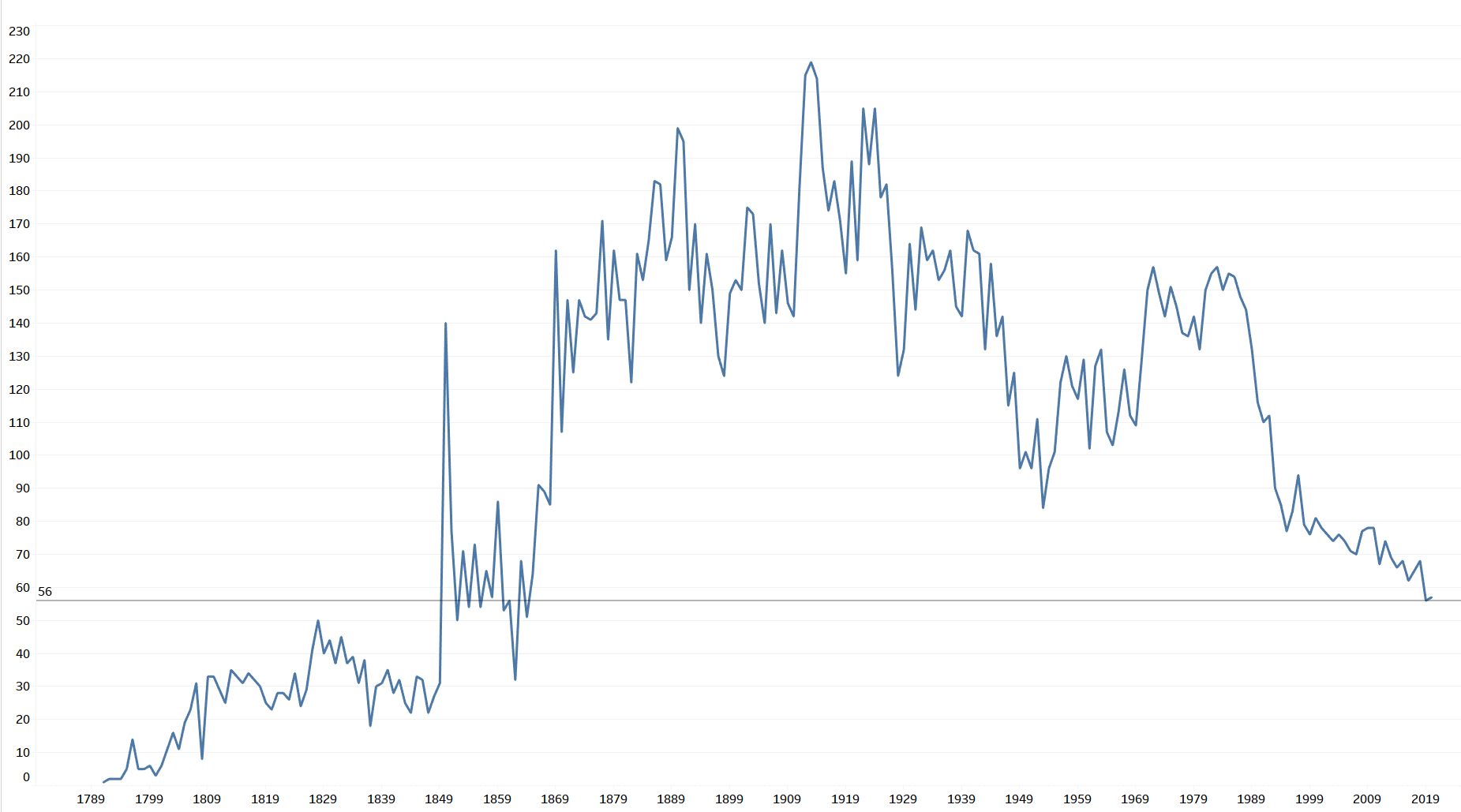

So it’s not just that the Court is hearing fewer and fewer cases each year (per the below graphic from Dr. Adam Feldman that shows the total number merits decisions by Term ); it’s that the Court is deciding a small number of carefully curated (and sometimes internally generated) questions within that self-selecting subset:

In a future issue, I’ll talk more about the universe of strategic and tactical behavior that the rise of certiorari has begotten, including how the Justices themselves manage the “cert. process.” The relevant point for present purposes is that the contemporary Supreme Court is defined by certiorari—by the discretion the Justices have to set their own agenda. As Professor Hartnett has put it, “the Supreme Court’s power to set its agenda may be more important than what the Court decides on the merits.” At the very least, understanding that today’s Supreme Court, with few exceptions, decides only cases the Justices agree to take up (and only specific questions within those cases) puts what the Court does decide on the merits into rather important perspective.

And whatever its merits, that perspective seems like a fitting place to begin any sustained discussion of the Supreme Court of the United States. We’ll pick the story back up next week…